The moment of reckoning has arrived.

On Friday, Altadis U.S.A., Davidoff of Geneva USA, Drew Estate and General Cigar Co.—likely the four largest companies in the U.S. premium cigar business—announced that they would not be exhibiting at the 2020 PCA Convention & Trade Show, formerly the IPCPR Convention & Trade Show.

There are a number of reasons for the decision, some of them extremely complex, but in short, it comes down to a few key points:

- The Companies are Not Getting the Same ROI on the Trade Show — Some of the four said exhibiting at the show was still profitable, one described the trade show as no longer profitable. Whatever the case, the costs are increasing and attendance and therefore buying is declining.

- The Companies Do Not Have a (Direct) Say about the Trade Show or Its Profits — I’m sure the Premium Cigar Association (PCA) would dispute both the premise that the companies have no say about the money and probably even whether the companies should have a say, regardless, it’s correct in saying that the final say rests with the PCA executive committee, which is comprised of five brick-and-mortar retailers and Scott Pearce, the organization’s executive director.

- The PCA Didn’t Address These Concerns Fully — The PCA’s statement, which was sent only to its retail members, didn’t address this topic. Pearce declined to comment on the accusations shortly before our initial article was published. I suspect that there will be disagreements about whether some concerns were addressed and to what extent. Regardless, the companies weren’t satisfied with whatever responses they heard, enough to go forward with pulling out.

Even if these four companies were the only ones to pull out—and they won’t be—it’s a devastating blow to the trade show and the PCA’s budget. Combined the four were 27,500-square-feet of booth space at the 2019 IPCPR Convention & Trade Show, or 18.17 percent of the booth space sold for the 2019 trade show floor. Furthermore, the four historically have purchased some of the PCA’s largest sponsorship opportunities. When all is said and done, these companies likely contributed over $750,000 to the PCA’s trade show revenue or directly to certain trade show expenses through sponsorships. Some of that money can be recovered, but some will likely be gone.

Regardless of what happens next, it’s a turning point in the history of the industry’s main trade show and one of the more monumental events in the cigar industry, probably the single largest since FDA unveiled its regulations for cigars.

A PROLOGUE

This is a very long article, the longest we’ve ever published.

The goal here isn’t some sort of PCA hit piece. My thoughts on the trade show and the PCA’s leadership have been published before and none of them have really changed. But, I also don’t think my thoughts, particularly on the latter, are all that unique.

Instead, my goal here is to provide some context to how the industry got here, why we got here and where we might go from here. Unfortunately, there are a number of different issues at play, oftentimes multi-layered and usually interconnected. Almost all of them have existed or have been building for quite some time. In fact, this isn’t the first time I’ve used the term a moment of reckoning in regard to the IPCPR/PCA and its trade show.

In the interest of full disclosure, I’ve had a lot of conversations with people on all sides of the issue—and there are more than two sides—for quite some time. That certainly escalated over the last year and further intensified in the last six months. I also had a lot of conversations last week with the four companies mentioned above, something that happens when an outlet tries to be the one that breaks news as monumental, in context, as this.

Unfortunately, the PCA didn’t give me a comment on Friday and to my knowledge, the PCA hasn’t given an on-the-record comment to any member of the media. In places where I can, I’ve tried to represent their side of the story, but in some places, I’m just not sure what it is.

You can read the full PCA letter to retailers here.

halfwheel is also a member of the PCA. Because of how the organization decided to deal with media, specifically online media, we are forced to be a member in order to attend the trade show. I would have preferred to not be a member and just give the organization money, but that’s what the organization decided, so I feel like it’s worth disclosing.

Depending on how you judge the JR/Altadis relationship, some or all of the four companies advertise with us, as do many of the other companies mentioned throughout. Hopefully, it’s clear at this point, that doesn’t matter when it comes to halfwheel.

If you decide to read the next 7,500+ words—and I wouldn’t blame you for clicking on cat videos instead—know this: this isn’t good for anyone and it’s not a good thing for the industry.

Chapter 1: THE TRADE SHOW AND ITS BROKEN MODEL

1. THE INTERNET IS A MYSTERIOUS PLACE

A handful of months into my cigar blogging career I published an editorial about what were then the hot button topics of the trade show: should we allow bloggers into the trade show and what are we going to be doing about all these companies giving discounts early?

That was a weird time, and a lot of what I said in 2010 doesn’t hold up today—my comments about Twitter are a bit cringeworthy now—but there are some obvious takeaways, most importantly, the trade show has had problems for a long time.

For many years, the Retail Tobacco Dealers of America (RTDA) Trade Show—that’s what the organization used to be called prior to 2009—was a place where the industry would gather and manufacturers would offer one-time discounts to retailers and introduce new product, oftentimes the only new product a particular company would debut in a given year. That model worked and the trade show grew and cemented itself as the event for the cigar industry over its now 88 years in existence.

Unfortunately for the trade show, the internet came along. What no one seemed to realize was that the internet would change everything, including cigars and cigar trade shows. Everyone understood the internet had changed the rest of the world, oftentimes in a positive way, but no one wanted to talk about the negative impacts it would have on the antiquated, err artisanal industry that is premium cigars.

Beyond the pesky bloggers, the internet meant that people looked at the world differently. Cigars or otherwise, people wanted more, they wanted it faster and in many cases, the information that people once paid for was now free. The internet also changed how cigars were sold and well before that 2010 trade show, the largest retailer of cigars was no longer names like Tinder Box or JR Cigar; rather, it was Cigars International, who had a catalog, but really was the master of how to sell cigars on the internet.

The internet also meant that consumers could easily compare prices, they could buy cigars and learn about cigars—but most importantly, do all of that from anywhere in the world.

By 2010, everyone knew that was possible. After all, the internet didn’t start in 2009.

But the problem for the trade show was that all those things consumers could do, retailers could do too. Retailers could search their emails to find whether a company’s current sale was better than its last one, they could text their representative and order cigars, and they no longer needed that sales representative to come to a store with a flyer to introduce a new product or promotion.

They, too, could do all of this from pretty much anywhere. They certainly didn’t need to fly to Las Vegas or New Orleans or Orlando to get a discount.

2. THE FOCUS ON DISCOUNTS

In 2015, the halfwheel team was asked if we would meet with some of the IPCPR’s leadership to talk about ways in which we could work together.

As a side-bar: some of those changes I am very grateful for. The IPCPR—only six years removed from having a real conversation about whether bloggers should be banned—wanted to help halfwheel. It understood that halfwheel was producing more content around the trade show than anyone else. It understood that people were reading our website and it offered to help make our trade show coverage better.

Most notably, it gave us access to a room close to the show floor to work out of, that’s evolved into the halfwheel bunker at the trade show and the PCA still helps to discount some of the costs associated with it. And for that, I—and the rest of halfwheel—are thankful, it’s made our trade show lives easier and allowed for us to produce better and faster coverage from the trade show.

But that meeting also showed that the IPCPR leadership still hadn’t fully given up on the idea of trying to get manufacturers to stop offering discounts before and after the trade show. It seemed clear to me in 2010 that the ship on stopping pre-show discounts had sailed. While the IPCPR leadership was largely telling us that it was moving on from the idea of trying to ban manufacturers from offering pre-show deals, it hadn’t. In fact, it still tries to stop manufacturers from using phrases like “IPCPR Deals” before the show starts, as if what they are called is the problem.

Even if it could get every manufacturer to stop doing this, it would be a bandage on the problem. The belief at the time was that the number of retailers was declining because they were unwilling to spend the time and money to attend the trade show if they could get the discounts without going to the show.

Some of that was true, but the discussions needed to go deeper. The problem wasn’t just the discounts, it was that trade shows, in general, were declining, something that continues to this day:

- Nikon, Leica and Olympus pull out of Photokina 2020

- Why the automakers are ditching auto shows

- Why Nick Hayek Pulled The Swatch Group Out Of Baselworl

The three shows mentioned above are global events for larger, legacy industries that are all in peril, and all multitudes larger than the PCA Convention & Trade Show.

For more niche industries and smaller shows, the decline is even worse:

- Industry tradeshow Interbike canceled for 2019

- National RV Trade Show canceled after more than 50 years in Louisville

There are a lot of factors as to why many trade shows are failing, but the internet—the thing that connected you to my 5,000+ words of text—is the largest singular cause.

3. The Inefficiencies

The main issues with the trade show aren’t related to discounts. But, the concept of using the trade show as a vehicle to discount products is particularly inefficient.

Three decades ago if a manufacturer wanted to offer all of its retailers a 15 percent off discount for a four-day period of time, a trade show—a place where as many people as possible are in a confined space—was probably the ideal time and place. Communicating with retailers was harder: mail, fax, phone, in person, and dial-up internet for those on the cutting edge. Even the process of receiving the orders was much more challenging; now those things can be done in seconds, sometimes involving no human interaction.

What certainly does not need to happen is a trade show where both the retailer and manufacturer spend money on hotels and travel, where the manufacturer needs to build a trade show booth in a convention center and where the manufacturer needs to ship all of these items all the way across the country and back. It’s a slower, more expensive process, and one that has more potential complications than doing it in a virtual, non-face-to-face manner.

Instead, that manufacturer could do it via a combination of email and phone calls. Just like many of you would rather buy your next vacuum off of Amazon—a process where the only potential human interaction is with whoever delivers the vacuum—many of these retailers would prefer not to have to buy their cigars in a face-to-face manner. As the number of reps and retailers that remember RTDA Cincinnati dwindles, so does the number of retailers that are vehemently opposed to the system of email and texts as a way to do business.

That’s the front-end efficiency, but the backend isn’t any better. As I’ve explained before, the trade show is a very inefficient method to fund an advocacy organization like the PCA:

The trends related to the expenses and revenue of the trade show is sort of like two ships passing in the night, albeit not in the traditional way that description gets used. Manufacturers complain that the cost of the exhibiting at the trade show continues to increase, dramatically. The PCA will then counter by saying the amount of money the IPCPR has generated from the trade show isn’t increasing much at all.

Both are true.

The problem is that the PCA sees very little, probably less than 20 percent, of what a company spends to exhibit at the trade show. The PCA gets the money the companies spend on booth space and for their membership dues. From some of the companies—particularly the larger ones—it gets additional money in sponsorship and advertising. There are some other instances of where the PCA might get money, like if a vendor gives the PCA a small commission on sales generated from its members, but that’s largely where the PCA’s revenue generation ends.

That means the PCA receives none of the money for when a company buys a physical booth, that goes to the booth company. It also won’t make money on the shipping of the booth, a cost that seems to increase annually. It’s also not going to make money—or at least a noticeable amount of it—for the setup and tear down of the booth. The costs associated with new signage, a coffee bar or the bottled water—those go to some entity that is not the PCA. All of the other basic travel costs—airfare, rental cars, taxis/Ubers, meals, etc.—those also go to someone else.

Chapter II: How We Got Here

There are many places this could start, but in true IPCPR trade show spirit, let’s start with complaining about attendance.

| Year | Stores | Badges |

|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 827 | 1,914 |

| 2015 | 745 | 1,896 |

| 2016 | 877 | 2,314 |

| 2017 | 752 | 1,920 |

| 2018 | 778 | 2,054 |

| 2019 | 771 | 2,085 |

| 2021 | 583 | 1,440 |

| 2022 | 707 | 2,036 |

| 2023 | 809 | 2,155 |

| 2024 | 850 | 2,200 |

1. WHATEVER THE OPPOSITE OF “MORE PEOPLE” IS

Here’s the deal: I don’t know how many people showed up at IPCPR 2019—or how many people showed up at any of the trade shows that preceded. Worse, I’m not sure anyone knows. Maybe the Sands Expo Center security team could leak me a tape?

Since at least 2013, we’ve pointed out that some of people’s perceptions about trade show attendance are probably false.

What I do know to be true: the trade show got bigger, a lot bigger. Some booths got bigger, a lot bigger. The number of companies exhibiting increased dramatically. Even if the exact same amount of people attended IPCPR 2015 as attended RTDA 2005, the trade show would look and feel less attended. The more space, the more people you need to fill the room to the same effect.

Most likely, attendance isn’t increasing, at least not over most of the last decade and definitely not over most of the last five years.

The real problem with all of this is the IPCPR has never wanted to figure out just how many people attended. They provide numbers related to attendance, but they’ve refused to implement the most accurate way to measure attendance: scanning badges.

Some years they’ve specified what the metrics they provide are based on, but it’s challenging to believe the numbers given when the organization has repeatedly been against collecting better data. I pointed out to people regularly things like, the size of the show is bigger and we can’t keep pretending this is 1999, but even I can’t defend how there were only seven fewer stores in 2019 compared to 2018.

While I don’t have an on-the-record statement about why they’ve haven’t scanned badges, or at least whatever the current reasoning behind why the PCA didn’t do it last year, the simple fact is if the PCA believed scanning badges would show an uptick in attendees, it would spend the money to scan badges.

Because of that, most people—including me and others at halfwheel—don’t believe the PCA when it says that 771 stores were represented at last year’s trade show. Even if I accepted that the 771 number was true for 2019, I’m not sure what sort of mathematical gymnastics took place to produce the data before last year. That means I have no clue what the numbers mean in context, which is far more important to me than the numbers in a vacuum.

2. BAD VENUE, THEN BAD DATES

For a number of reasons, following the 2016 trade show, the Sands Expo Center—the convention center located at the Venetian/Palazzo casino and hotel—informed the IPCPR that its trade show would no longer be welcome back. I was told that a primary issue was attendees smoking in areas where they were told not to, repeatedly.

Grown men and women—some of you reading this article and others probably watching the aforementioned cat videos—taking selfies with lit cigars next to “no smoking” signs, then posting them to social media and tagging the venue. That’s before accounting for some distinct gestures in said pictures. It’s all fun and games; until you are staying at the Westgate.

Someone started a rumor that the real reason was because Microsoft wanted to use the Sands for the dates IPCPR had reserved, but as it turns out, the main part of the Sands was verifiably empty during the 2017 IPCPR Convention & Trade Show and Microsoft didn’t have an event going on at the Sands during any of the dates around it. Just so we are clear, I actually went and looked for myself that year: no trade show going on, no Microsoft. I even checked the calendar.

That led the trade show to move to the Las Vegas Convention Center, which is not attached to any hotel. The Westgate became the official hotel of the trade show, a move that seemingly no one enjoyed in 2017 and things only got worse in 2018. Shortly before the trade show was set to begin, a Norovirus outbreak occurred at the Westgate, which forced the IPCPR to move events out of that hotel.

Before the Norovirus outbreak the IPCPR had already decided to move the 2019 trade show back to the Sands. While the majority definitely wanted to be back at the Sands/Venetian, the problem was the dates that were selected weren’t ideal.

- IPCPR 2019 — June 29-July 2, 2019

- IPCPR 2020 — June 27-30, 2020

The IPCPR did survey people about where they wanted to be, but it failed to mention that all things weren’t equal. The trade show could return to the Sands, but the dates would need to be much earlier and much closer to July 4. That was never made clear on the survey, but once the change was announced, many were up in arms.

That led to declining attendance in 2019, a narrative that started before the trade show and actually rivaled CigarCon as the top talking point by the conclusion of last year’s trade show.

3. The IPCPR-CRA Merger

When all is said and done, the most baffling part of the timeline that got us to these events will be the renewed merger discussions between the IPCPR and Cigar Rights of America (CRA). It’s not that the merger was a baffling idea, but I doubt anyone thought the discussion—particularly a failed discussion—would be as consequential as it may have been.

The IPCPR, now PCA, claims itself to be a retailer’s organization, though with PCA it’s trying to also claim to be more than that. While it’s controlled by retailers, the money largely comes from the trade show, which in turn comes from manufacturers. The CRA publicly describes itself as an organization trying to engage consumers about legislative issues surrounding cigars, but functionally-speaking, it’s largely funded by 10 cigar manufacturers and its board is made up of some of those manufacturers and a single consumer.

I’ve heard a lot of different takes on just how optimistic people were that the merger would happen, but it seemed by late March that the idea of a combined organization controlled by a “superboard” was not realistic. The PCA side didn’t seem willing to give up much control or many—if any—of the seats on its executive committee, which essentially ended the idea of this being a merger of equals. In conversations with people on both sides of the merger, it was clear in April that the two sides were discussing two different ideas. By early May, barring a Hail Mary, it was obvious that the IPCPR would be going through with both its rebrand to the PCA and the introduction of CigarCon without a merger/absorption of the CRA.

Unfortunately, four companies, maybe five, were freaked out. The four companies that pulled out were far more concerned about the merged organization happening than anyone I spoke to that was directly involved with the negations. In a world of the merged superboard, those four companies would presumably have no say in both the trade show as well as the profits generated from the trade show.

I’m sure that the CRA/PCA sides would say that there would have been some advisory position created, but in terms of the decision-making, the potential outcome was clear. To some degree I understand it, the non-CRA companies weren’t involved in the negotiations, why should they get a seat?

Those four companies—along with CLE and Perdomo—were already working together to develop a joint comment to FDA regarding substantial equivalence, which they submitted in July. At some point during those discussions, they clearly also talked about what was happening around them.

It should be clear, the CRA/IPCPR merger wasn’t happening in complete silence. The other manufacturers knew that the often-talked about merger was back on the table, probably as early as late 2018. There were also liaisons between the discussions and the other companies.

I believe that even without the CRA/IPCPR merger talks at least some of the four companies would still not be exhibiting at the 2020 trade show. But, I’m not sure it would have been all four. There was a sense of urgency that the four had once those talks began, one that I always thought was an overreaction given just how unlikely the merger seemed, how unlikely the merger had always seemed.

4. CigarCon

The PCA rebrand, some of the new goals of PCA—like greater outreach and diversified income streams—and CigarCon were all part of the negotiations that took place between the two sides. But the IPCPR made it clear to everyone involved and aware: it would go forward with these changes with or without the CRA merger.

But a proposed CRA merger wasn’t the same as CRA support absent a merger.

Like the CRA/IPCPR merger, the concept of a consumer day wasn’t new. The IPCPR had tried to introduce it in 2013, but ended up tabling the issue after gathering—presumably negative—feedback. Both sides, independent of one another, probably underestimated just how opposed the rest of the industry would be to CigarCon, but the PCA definitely didn’t see a scenario where some CRA members would fail to publicly back them.

The four manufacturers were consulted and informed about CigarCon, as were other non-CRA members like Gurkha and Miami Cigar & Co., and some even had direct input at various points over the last decade through the IPCPR’s Associate Members Advisory Board (AMAB). I’m not sure how much each of the companies were consulted individually, but they weren’t in the dark about was being proposed.

But that all became irrelevant once the PCA rebrand and CigarCon were announced. The bulk of retailers seemed to be against the idea. Few manufacturers were willing to go out on a limb. Even consumers didn’t seem overly excited about CigarCon.

Most problematically, as I wrote last summer, this just furthered the narrative that the IPCPR, now PCA’s, executive committee was making massive changes by themselves.

They didn’t do it by themselves. The CRA, or at least some of it, was presumably on board at one point. Some of the non-CRA members were supportive of the plans. But there’s no evidence that the IPCPR asked much of its membership or smaller manufacturers or even consumers what they thought. It then lied and said that what it was doing was to gather feedback. In fairness, part of the goal was to gather feedback, but the idea that IPCPR intended to not do CigarCon 2020 is asinine.

CigarCon was something that should have been stopped like it was in 2013, but in the end, it just seemed to get nearly everyone a bit more pissed off at the PCA and increasingly, the blame was now being placed on the executive committee.

5. Maryland

You may have heard some rumblings that the decision by the four companies was due to catalog/online sales and excise tax.

Two of the four—Altadis and General—are owned by companies that also own three of the largest catalog/internet retailers: Cigars International and Thompson (both owned by General’s parent STG) and JR Cigar (owned by Imperial Brands, parent of Altadis.) Davidoff sells cigars directly to consumers via its online store, which I can’t imagine is one of the top 25 largest online retailers of cigars. Drew Estate has no retail operation to my knowledge.

If 1,000 retail stores showed up at the trade show—last year was 771 according to the PCA—no one would be complaining, let alone pulling out of the trade show. But yes, there are other issues at play, though they aren’t the main ones.

One of them does relate to excise tax, specifically, accusations that an outside lobbyist who was working with the PCA lobbied in the state of Maryland to have the excise tax on cigars applied to orders placed from out of state.

Arthur Zaretsky, the owner of Famous Smoke Shop—the largest independently owned retailer in the cigar industry—said that he will not be attending the PCA Trade Show because of this, marking the first time in 50 years he has not attended an RTDA/IPCPR/PCA trade show.

His issues are specifically related to the alleged lobbying:

I am tired of supporting those who seek to damage my business to increase their own. Recently this all came to light when I learned that the PCA spent time and money to increase taxes on cigars. Yes! Under the banner of a “level playing field”, the PCA lobbied to increase taxes, but only on remote sellers like me. So here you have a hypocritical organization, which is out to hurt and/or destroy a part of the industry. Why? We are not your enemy. Your business will not be better if we disappear. Prices will skyrocket and few will be able to afford $12-$20 cigars.

You can read Zaretsky’s statement in full here.

The PCA declined to comment on Zaretsky’s claims.

If it’s not true, I’m not sure why the PCA wouldn’t deny the accusation. If it was true, it’s not a great look. And, there is some real evidence that the IPCPR has considered this in the past.

The PCA is an organization designed for brick-and-mortar retailers and its retail membership requires that you must have a physical storefront. While I certainly understand why many would want the internet retailers to have to pay the same taxes, I’ve argued that the long-term survival of brick-and-mortar retailers is dependent on their own businesses and business practices, not their online competitors.

As far as what this might have had to do with the decision to pull out of the trade show, it’s unclear. I’ve heard from the four companies that they don’t believe the issue was ever discussed with the PCA as part of their discussions; once again, the PCA isn’t commenting.

6. THE COMMERCIAL STRUCTURE

One thing that isn’t mentioned in the press release from the four companies is that some of their issues extend much beyond the PCA and its trade show. Those companies would like to see changes to the wholesale pricing model that exists in the cigar industry.

They aren’t alone.

Manufacturers of all sizes are becoming increasingly more agitated at the discounts that retailers are getting and/or asking for. While I certainly understand that we should stop living in a world where everyone pretends keystone margins are the norm seven days per week, this isn’t the retailers’ fault.

Manufacturers can—and do—say no to offering discounts. They can say no to things like more Tobacconists’ Association of America (TAA) virtual trade shows, another common complaint. They can also manage their inventory to where there aren’t multiple examples of companies moving inventory at or below cost.

These complaints aren’t the reason why these manufacturers are walking away, but they are part of the problem.

Chapter III: The Decision(s)

1. “The Colluders”

That was the name given to the five companies by the PCA: the colluders.

Honestly, I would have written the entire article just referring to them as that as it’s better than “the four companies,” but I don’t think that it’s a fair description. These five companies, the four plus Perdomo, colluded just as much as the IPCPR and CRA were attempting to collude when they were discussing the merger.

At some point around or after the 2019 IPCPR Convention & Trade Show, Perdomo changed its mind. Perdomo’s decision to exhibit 2020 shows some evidence that the colluders weren’t in some sort of suicide pact where if one goes we all go and vice versa. Otherwise, Perdomo’s decision would have stopped the whole thing.

There are similarities with the four companies that pulled out, but I do believe that the decisions were made independently. Some told me before the start of the 2019 trade show that they were out for 2020. Others seemed to be a bit more optimistic. At least one of these companies has been hinting about not exhibiting to the IPCPR/PCA for the better part of the last decade.

Drew Estate’s presence at the trade show has dramatically expanded over the last five years; General Cigar Co.’s has been almost equally scaled back over the same period of time. When asked individually, the companies gave different answers to most of the questions I asked them. Some said the trade show was still profitable, one said it wasn’t. Some said they could have scaled back, others said it was an all or nothing type of decision.

My point here is, this isn’t a monolithic block of companies any more than the CRA is. These companies, like the CRA manufacturers, have similar goals; but there are very different ideas on how to achieve them other than step one: don’t exhibit in 2020.

2. “Met With Silence”

Attempts to discuss ways to reverse the downward trends in relevance, attendance, membership, and category growth have been met with silence.

That’s straight from the four companies’ press release.

It’s also not true.

When pressed, the companies acknowledged that it wasn’t “silence,” at least not the definition of silence as I understand it. The two sides met, some of the questions might have even been directly responded to. Some of them were not.

The PCA’s statement sent to retailers didn’t address this point or really any of the points raised by the four companies in their joint press release. I asked Scott Pearce directly about this, he declined to comment about it on Friday and the organization still hasn’t responded to me or, to my knowledge, to any media with any statement.

Regardless of what transpired, I never got the sense from either side that anything was being resolved in those meetings. It would be fascinating to know how the PCA felt it was doing in responding to the manufacturers. Did it feel like it was doing a good job? Did it feel the questions were inappropriate? Did it believe it would ever get to this? Then again, I’d just like a response about the claims of silence.

Whatever the case, I think many—including me—felt like the four companies weren’t actually going to pull out, at least not completely. They could scale back, they could see if the better dates helped, they could do something. But even when the signs said otherwise, it still was tough to believe.

3. Why Now?

The four companies acknowledge that their issues aren’t entirely new. But then again, the IPCPR/CRA merger wasn’t a new idea, declining attendance has been a narrative since my first trade show in 2010 and the costs increase nearly every year. So perhaps 2020 was just a breaking point.

All of those reasons would be considered offensive reasons to leave now; if we want to talk defense, there’s certainly a reduced amount of perceived risks.

The companies haven’t admitted it and I doubt they ever would, but I think they watched the lack of fallout from Villiger’s decision to pull out last year and then saw the CigarCon announcement backfire—and then concluded the potential fallout just wasn’t the scary thought that it used to be.

Normally if a company decides not to attend the IPCPR Convention & Trade Show, it raises eyebrows for whether that company will be around. But Villiger, a company whose booth never looked busy, seemed to be celebrated for not going.

Perhaps most importantly, the companies decided it wasn’t going to get better by continuing to attend. Some of that’s in the various points above, some of it’s probably related to the PCA’s responses—or lack thereof—and a lot of it is related to the financials. After talking with them, it seems quite clear they were more concerned with the potential PR fallout than they were with missing out on the events and business at the trade show itself, which is a pretty grave sign of where things are at from an ROI perspective.

If one was going to Monday morning quarterback how this went down, the PCA probably should have said something earlier. By mid-December at the latest, the organization knew this was an almost certain outcome. Within the last month, the PCA began moving companies into the spaces it had reserved for the four companies, a pretty clear sign it knew it was time to move on.

Something along the lines of: these companies have told us they aren’t committing since last spring, it’s been seven months, we hope they show up but we won’t let them hold the 2020 trade show hostage by not making a decision.

It wouldn’t have stopped all the fallout, but it could have at least shifted the narrative from an offense/defense paradigm.

Chapter IV: Going Forward

1. PCA 2020 Will be Full?

Per the PCA’s Friday night statement to retailers:

The PCA 2020 show will be full, with the family-owned manufacturers who support the brick and mortar retailers and whose products fill our humidors.

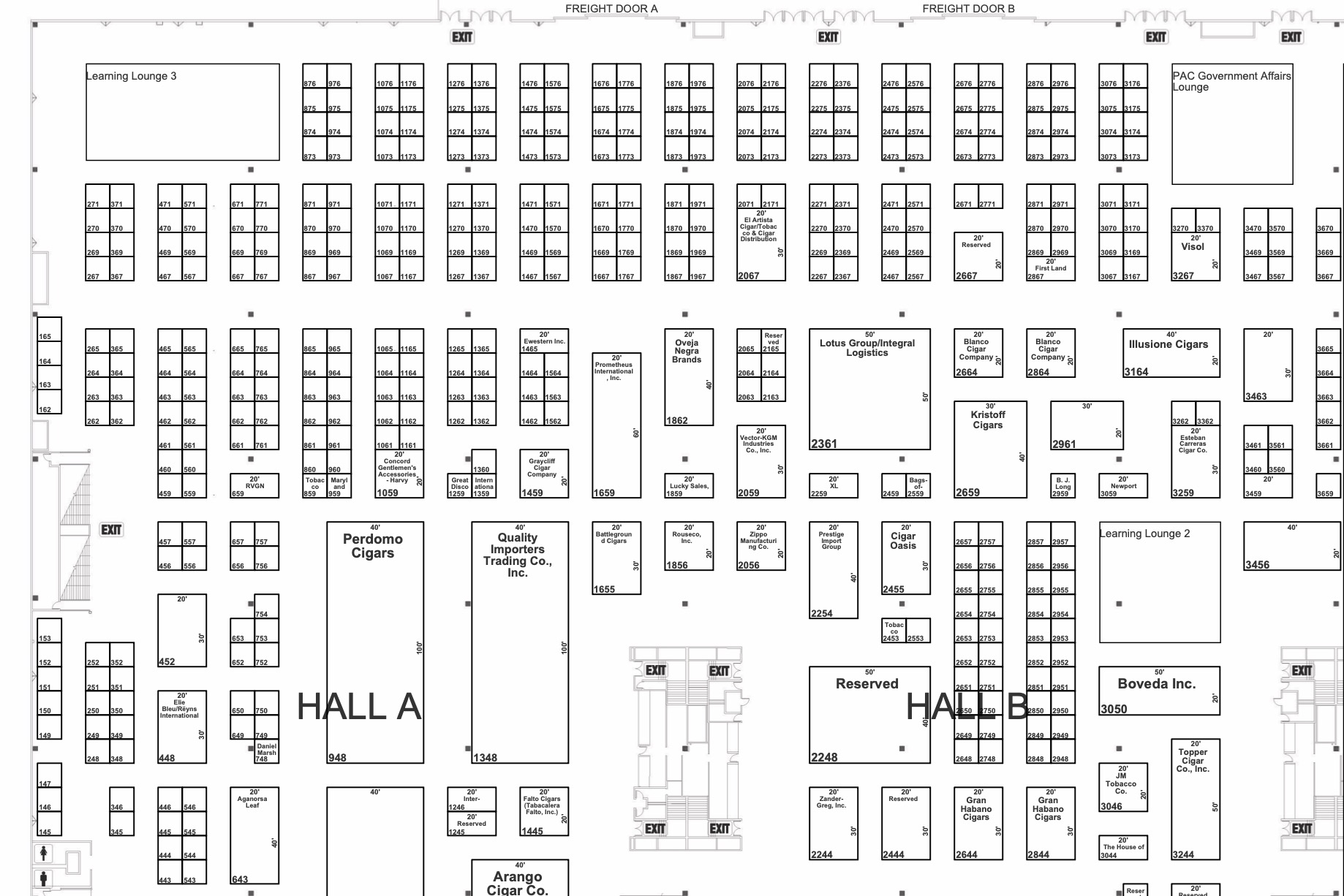

I do not have all the metrics the PCA has about how things are trending for 2020, but I don’t know how the above statement could possibly be true. The IPCPR Convention & Trade Show wasn’t full last year and hasn’t been “full” in a while. For context, it seemed the organization sold roughly 94 percent of the space it tried to sell as per this map.

The PCA’s statement also said that ”110,000 square feet of space booked by hundreds of family-owned companies.” I have no idea how that could be possible:

- The PCA 2020 Exhibitor List is at 90 Companies — I understand that this list is probably not 100 percent accurate, but 90 companies is 110 away from “hundreds.” Furthermore, the aforementioned IPCPR 2019 map only shows 211 companies. If the PCA is trying to claim “hundreds” means anything over 99+, yikes.

- That Would be 73 Percent of 2019 — I counted 151,300-square-feet of booth space for companies at last year’s trade show. That’s not the total size of the space or even the total amount of space that could be booked. That was what this map shows as booked by exhibitors. The 110,000 number would imply that they’ve already booked 73 percent of the square footage they did last year, better yet, it would imply the PCA is roughly 91 percent of the way to being booked to what it sold last year minus the four companies.

- It (Probably) Doesn’t Add Up — Here’s a math exercise:

- 151,300-square-feet — The space sold at IPCPR 2019

- 9,500-square-feet — That’s how much unsold booth space, i.e. completely blank booths, I could count on the 2019 map. That’s not to say that there isn’t more space available, but I don’t think there’s that much more space. That number doesn’t include any of the spaces in color, which are presumably non-revenue trade show space.

- 16,000-square-feet — PCA 2020 will expand the meeting/party areas in Hall C a bit to remove roughly 16,000-square-feet of sellable booth space, most of which was actually sold on the 2019 map.

- 6,900-square-feet — A recent map I saw from last week showed three PCA Learning Spaces on the main trade show floor, i.e. space the PCA can sell unlike Hall C.

- 110,000-square-feet — What the PCA claims it has already booked. The first two numbers would imply the PCA, with 100 percent space booked, could have sold 160,800-square-feet last year.This year, that number would reduce to 144,800-square-feet through the Hall C reduction.If you subtract the 6,900-square-feet of Learning Spaces, you are left with 137,900-square-feet.That would mean with the 110,000-square-feet of space allegedly booked, the PCA would only be able to accommodate the four companies that have pulled out and a grand total of 400-square-feet more of added booth sales.

If the PCA was anywhere close to having the space abandoned by those four companies and just 400-square-feet, it would be boasting about it with phrases like “almost sold out” or “on track to be bigger than last year,” statements that would almost certainly be closer to the truth than what was in that release.

Furthermore, the top half of a map from late last week (above) easily shows more than 30,000-square-feet—and very likely close to 40,000-square-feet—of unmarked booths on just the top half alone. And to be clear, I didn’t count all the blank space, that was what I came up with in about a minute of selective counting part of the show floor.

2. Practically Speaking…

Those are numbers and they are hard to make sense of.

Beyond that, I don’t see how anyone could think that the fallout is going to be just contained to those four companies. Some smaller companies have said they are out, La Flor Dominicana told Cigar Aficionado it was going to make a decision this week, a representative from A.J. Fernández told Patrick Lagreid that as of now, it was planning on not attending but hadn’t completely closed the door.

Other companies, including some that are listed amongst the 90 on the PCA 2020 exhibitor list, have told me that they actually haven’t paid their deposits and I suspect some of them are very much considering not attending.

I don’t see a scenario where the fall out just stops. There’s no reason to believe—other than some challenging to understand PCA numbers above—that PCA 2020 will be better than IPCPR 2019, which was already being described by many as the worst trade show in recent memory. I’m not sure if it was the worst, but that was a pretty common narrative.

No matter the assurances from Alec Bradley, Arturo Fuente, J.C. Newman, Tatuaje and others about attending the trade show, they aren’t going to counteract what the four larger companies did, particularly in a world where retailers themselves are losing interest in the show. The four largest companies in the trade show all pulling out at once is the opposite of a ringing endorsement.

Furthermore, the IPCPR hasn’t been able to build excitement about the trade show in the immediate months leading up to it. Some of that is entirely not their fault. The widespread and longstanding practice of sales reps telling retailers that the upcoming trade show is going to be terrible is about as counterproductive as any act; but if it was happening in 2016-2019, I can’t imagine what’s about to be said in the coming months.

I think the hype around TPE is neither grounded in TPE’s track record nor reality, but TPE 2020 has more excitement about it than PCA 2020. Remember: we’re talking about TPE here, a trade show that is only a few years removed from having vendors selling fake urine.

In a vacuum, being more than a week removed from July 4 should help, but the problem is IPCPR 2018 began on July 11 and that only attracted 778 stores, according to the PCA.

At this point, if attendance drops 10 percent it would be a win, probably a massive win. Quite frankly, if retail attendance can drop less than 18.17 percent that might be a win. But anytime regression is being talked about as a win, you aren’t actually winning.

3. The Trade Show As It Stands

I suspect the fallout from all groups of attendees will be noticeable. I just don’t think there’s much—outside of better dates—that is going to convince more people that didn’t attend or exhibit last year that 2020 is the time to do so.

My guess is that most companies will wait until after the conclusion of the 2020 trade show and take stock of what has happened and what they’d like to do. Barring an uptick in attendance, I suspect the 2021 trade show will be in jeopardy.

It’s not that I’m rooting against the trade show, far from it. In fact, it’s halfwheel’s busiest and most important time of year. I want as many new products from as many companies as possible. But I just don’t understand how anything other than a downturn is plausible.

There will be a 2020 trade show. I’d venture to guess that there will be 150-175 exhibitors. Some of them will be frustrated, probably more so than last year. Many of them will say “this is the last one,” some of them might actually be serious this time around.

The real question is whether the PCA leadership has any plans for substantial changes already in the works. Does CigarCon get seriously proposed for 2021? Will the trade show consider cutting a substantial amount of space? Will there be another attempt at addressing the concerns of the four companies and the others who exit?

I don’t know, but that’s what to pay attention to for the next five and a half months. Until the doors open on July 11, everything else is just speculation, including the last thousand or so words of this article.

4. 2021 & Beyond

I’ve argued that the trade show should be smaller. Rather than repeat it, scroll down to point #10 and then come back here.

That’s my idea, one that’s smaller and less about discounts. I’d like to see serious commitments to education, a more professional environment for collaboration and something that focuses on tomorrow, not today.

None of that can happen without removing the focus on selling. So much of the trade show’s problem is the attitudes and expectations people have of the event. They expect it to be full of discounts they can get at home, so why go; they expect no retailers to show up by day 3; so why not leave early; and they expect the seminars to be useless, so why not go to the bar.

Convincing the retailers that the trade show isn’t going to be a place for you to offset their travel expenses by mass discounts is going to be tough, but it’s not impossible. It works at TPE for an audience that is far less premium than the PCA, but the selling part has to take a backseat.

That’s my hope, but I think it’s going to take a lot longer than 2021 to get there.

My speculation is that the 2021 trade show looks more like a scaled-down IPCPR Convention & Trade Show than it does of something transforming. Perhaps CigarCon becomes a thing for 2021, I mean, at a certain point you have to try something new.

Hopefully, the conversations are more productive, but if history is any indication, it’s going to get worse before it gets better.

5. For the PCA

Whatever you might think of any of what’s happened, I’m not sure how one can argue the PCA—as currently structured—should continue. That’s the view of the four companies, that’s the view of many CRA members I’ve discussed it with and I imagine that’s also the view of many of the retailers. Last summer, 59 percent of exhibitors surveyed said they had lost faith in leadership, I can’t imagine that the number of people who thought the PCA didn’t need leadership change decreased between Friday morning and Friday night.

For as head-scratching as many of the decisions the PCA leadership has made, the organization is still quite valuable. In 2018 it reported revenue of $4.55 million, $3 million of which came from the trade show, and ended the year with $5.57 million in net assets. That said, the organization still reported a $386,000 loss and a drop in net assets of over $1 million.

The organization is controlled by its executive committee, who—understandably—has been unwilling to give up much, if any, power—especially when we are talking about final decision-making and giving it to manufacturers. There is no doubt that the four manufacturers want some of that power. When asked, three of the four made it clear that changing how the structure of how the organization makes decisions is a key barrier in getting them back to a trade show.

I suspect not much will change between now and PCA 2020, but once everyone takes stock of what does or doesn’t happen in Las Vegas, I think we’ll know how serious the rest of the manufacturers and retailers are about changing.

My personal hope is that the decisions around the trade show are being made by a diverse group of people in the cigar industry: big/small, manufacturers/retailers, online/brick-and-mortar; maybe even media, just not me.

The retailers deserve to have an organization of their own, but I don’t think that should include having the bulk, let alone nearly all of the power over the trade show.

Decisions around the trade show should be made by the people who risk the most amount of money. The retailers spend money at and around the trade show, but most of that money is in products—goods they then sell—and a lot of it is done via a discount, a net positive for the investment in the trip to Las Vegas. For the manufacturers, it’s increasingly become hoping and/or praying that the retailers show up. That’s not good.

Chapter V: There Were No Winners

So much of this decision, particularly to those close to it, has been viewed in a vacuum of us versus them.

If there were 10 new companies ready to take the 27,500-square-feet of space the four manufacturers are walking away from, the PCA and those close to it would have a much different response. If there were 1,000 retailers at the trade show last year, the four companies never would have walked away in the first place.

I’m not sure what those four companies possibly could have won last Friday. They didn’t endear themselves to anyone—even those that support their decision. No one is saying “how brave they are for standing up to the PCA.” At best, the companies made a business decision. At worst, people think the companies are intent on destroying their business or their industry.

The PCA didn’t win.

The CRA didn’t win. The small manufacturers didn’t win. The retailers didn’t win. The media, including halfwheel, didn’t win. TPE didn’t win.

Even the Venetian, a casino, somehow loses.

Everyone, including probably me, looks worse for it. (I literally look worse because of a lack of sleep.)

While there weren’t any winners, the losing may not be done. Regardless of your thoughts on whether the PCA needs a regime change, whether the four companies should be banished from all future shows or whatever, just about everyone agrees the trade show is in trouble and it’s been that way for quite some time.

It would be so problematic if, after all of this, nothing changes. I don’t think that option is still on the table. The “transformational change” those four companies talked about is already underway, at least in a negative sense. It’s just a question of if the outcome is a better trade show than the one those four walked away from.

These are complicated, longstanding issues. Ones that aren’t going to get solved in six months and aren’t going to get solved by six people. Advisory committees and proxies aren’t the answer, and shutting down the PCA trade show just to rely on TPE, TAA and Intertabac only diverts most of the problems.

None of this might matter in the long run. At some point there might not be an executive committee worth being on, a trade show worth fighting over or an event worth 8,000 words to write about.

There’ll just be apathy, frustration and blame. Three things the trade show already has in spades.

FAQ

I’m not done, here are some answers to some very specific questions.

THE PCA SAID THE FOUR COMPANIES ONLY REPRESENTED 12 PERCENT, YOU SAID OVER 18 PERCENT. WHAT’S WITH THE DIFFERENCE?

I’m not sure where the PCA came up with its number. Once again, if it was talking to media, that would help.

I literally counted booth by booth and came up with 151,300-square-feet worth of booths that were designated for a company at IPCPR 2019. I’m willing to admit that there might be some human error in that number, counting the booths was a lot more challenging than one would expect.

I then counted what the four companies had used in 2019, 27,500-square-feet, and did a simple fraction.

The PCA’s number wouldn’t seem to be the percentage of total potential booth space, which is what makes it odd. Bigger companies pay less than smaller companies on a per square foot basis, so perhaps those companies only represented 12 percent of potential total revenue from booth sales. I honestly don’t know.

In my mind, the best metrics would be how much money and space those companies accounted for compared to the total revenue and size of booths that were sold. I don’t think there’s a scenario in either instance where the answer to either is 12 percent.

WHY ARE SOME COMPANIES ANNOUNCING THEY ARE ATTENDING PCA 2020?

You can read the full CRA statement published in full here.

Many of those companies are part of the CRA, including:

- Alec Bradley

- Arturo Fuente

- Ashton

- J.C. Newman

- La Flor Dominicana

- My Father

- Oliva

- Padrón

- Rocky Patel

- Tatuaje

I could probably write another 3,000 words just on the CRA’s connection to all of the news, but I’ll try to keep it brief.

First, the CAA—of which the four companies pulling out are all members—the CRA and the PCA are all plaintiffs in a joint lawsuit filed against FDA. The CRA and IPCPR are more or less aligned in that lawsuit, the CAA—which also represents machine-made cigar companies like Swisher—isn’t always in the same place. Two of those places are in regards to: a. the CAA’s stance on a premium cigar exemption; b. paying for the lawsuit.

While the four companies, plus CLE and Perdomo, filed joint comments seeking an exemption for premium cigars from FDA regulation, that’s not the view of the CAA as an organization; some of its non-premium cigar members don’t believe in an exemption for premiums. Furthermore, the premium cigar-producing CAA members have a different position about flavored cigars compared to that of the PCA/CRA. The CAA and the CRA/IPCPR side disagree about what conditions existed or didn’t when it came to who would pay the bill. All sides agree that it was to be split evenly, but the CAA contends it was conditioned on certain legal arguments not being pursued. The CRA and PCA sides disagree with the CAA about those conditions.

#acronyms

The CRA and PCA leadership and stakeholders aren’t always the best of friends. But the enemy of my enemy is my friend. The staunch defense from some CRA members is probably genuine, but for some, it’s a money thing. The CRA side has, rightfully, argued that its members pay a higher percentage of the legal bills than companies who aren’t members of the CAA or CRA. (Obviously, the aforementioned dispute means some CRA members would probably argue they pay more than some of the CAA members.) Reduced trade show revenue means that number is likely to only increase. So, it’s understandable that the CRA companies are not only upset about the four pulling out, but are also trying to stem anymore fallout.

In a world in which trade show profits weren’t directly tied to the legal bill I would be fascinated to see what the position of these companies would be. I’m all but assured that at least one of them would have already pulled out and I imagine others would be following them.

ISN’T COLLUSION ILLEGAL?

In certain instances, yes.

Two quick points: a. the name “the colluders” wasn’t something that some prosecutor termed, that was a name I’m told originally came from the PCA side to describe the five companies and then spread; b. there’s evidence that shows that the companies actually had an attorney present at meetings to prevent any risk of doing anything that would be considered illegal.