Earlier today, a panel convened by the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) published a much-anticipated report called Premium Cigars: Patterns of Use, Marketing, and Health Effects. The report is one of the most comprehensive studies of premium cigars and their potential health effects ever commissioned, though—in my opinion—it raises more questions than it answers.

You will hear and read from people on all sides of the issue of premium cigar regulation, and many of them will have their own take on the report. To be honest, it’s somewhat of a fitting reaction to the report, which itself is largely a study of various existing data sets.

For example, here’s the headline Premium Cigar Association (PCA) used when describing the report:

BREAKING NEWS: NASEM Validates PCA Call for a Premium Cigar Category

And here’s the headline from NASEM’s own press release:

Premium Cigar Ingredients as Harmful as Cigars and Cigarettes; Health Effects Depend on Frequency, Patterns of Use

These two groups are both talking about the same exact 521-page document; yet, the leading description is quite different depending on the perspective.

1. WHY DOES THIS REPORT EXIST?

As fitting as the intro is—see point five—the logical place is to start with why this is happening. That answer is a bit complicated, but the short version goes something like this.

In 2014, the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) announced the deeming regulations, a framework to regulate certain types of tobacco products—basically, anything that wasn’t a cigarette or smokeless tobacco—for the first time. The list of products was led by e-cigarettes and vaping products, though cigars, pipe tobacco, hookah tobacco and others were included.

As part of the legal process for FDA to introduce new rules, the agency needed to announce what it intended to do and ask the public (this includes citizens, industry, health groups, really anyone) for input on said plans. FDA took an unusual step of asking people to provide feedback on whether it should regulate all cigars the same way (Option 1) or regulate mass-market/machine-made cigars but not regulate “premium cigars” (Option 2). In doing so it also asked for input about what might constitute a “premium cigar,” etc.

FDA ultimately decided to regulate cigars the same way. The first parts of the regulations went into effect on Aug. 8, 2016, though many parts didn’t have deadlines until well into the future, some three years away.

June 2016 — Cigar Trade Groups Sue

Three cigar trade groups: Cigar Association of America (CAA), Cigar Rights of America (CRA) and the International Premium Cigar & Pipe Retailers Association (now known as the Premium Cigar Association) filed a joint lawsuit against FDA’s deeming regulations.

July 2017 — Health Groups Sue in Maryland

Almost immediately after the regulations were announced, FDA began delaying some parts of the rules. There were many parts of the deeming regulations that the agency said still needed to be finalized when it announced the “final rule” and a coalition of anti-tobacco groups and pediatricians sued FDA in a federal court in Maryland. Their argument was that FDA was violating the law by unilaterally deciding to delay things.

May 2019 — Health Groups Win in Maryland

The main delayed deadline the health groups sued over was the premarket tobacco product approval process. (This is a poorly named process as it applies to products that are already on the market and not just products trying to enter the market.) While the lawsuit was largely about FDA’s delay—meaning that e-cigarettes weren’t being regulated—the impacts of FDA losing the case meant that the cigar industry was affected.

In July 2019, a federal judge in Maryland moved up FDA’s then plan for product approval applications to May 12, 2020 from their original due date of August 2021.

COVID Delays Deadlines until September 2020

This seems fairly self-explanatory.

August 2020 — Product Approval Delayed for “Premium Cigars”

While all this is happening the Cigar Association of America et al. v. United States Food and Drug Administration et al. case has continued. Ahead of the September 2020 deadline, it seemed likely that FDA was going to lose at least one more court decision in this litigation—which has already reversed FDA’s plans for warning labels on cigar boxes and delayed other parts of the deeming regulations—and it seemed like FDA knew it.

In a somewhat bizarre move, FDA proposed delaying the product approval process (largely referred to as substantial equivalence) for “premium cigars.” The part that seemed troubling for FDA dates all the way back to 2014, Option 2. When FDA announced the deeming regulations, it asked people to comment about whether it should or should not regulate “premium cigars.” Because of the federal rules that govern FDA, the agency was then forced to respond to the comments it received. In this case, the plaintiffs argued that FDA did not and instead dismissed the comments without actually having much evidence that supported the decision it made. Furthermore, it didn’t help that Judge Amit P. Mehta, the judge who had been hearing this case since 2016, had stated on numerous occasions that he thought FDA has been unfair to the premium cigar industry due to both its lack of research before enacting the rules and also the various delays combined with a lack of information since the rules went into effect.

So less than a month before the premarket product approval applications were due for cigars and other tobacco products, the judge approved FDA’s proposal. The agency delayed substantial equivalence deadlines for “premium cigars”—basically any large cigar that isn’t flavored—and would further study the issue of premium cigars and consider a streamlined process specifically designed for “premium cigars.” The reason for making this proposal—as pointed out by the judge—was pretty clear. FDA needed to delay the ruling until after the facts had changed because it seemed likely that if Judge Mehta had to rule in August 2020, he was not going to be happy ruling for FDA.

Of note, Mehta has ruled in favor of FDA while also chastising the agency, but this seemed like a culmination of frustration combined with an area where FDA may have actually been in the wrong.

So after the plan was approved, FDA needed to study the issue. To do so, it decided to commission a report from NASEM, which then convened the aforementioned panel.

2. Who’s on the Panel?

Not anyone you’ve heard of. Well, most likely.

There are 14 people on the committee, though one resigned midway through. All of them are professors at U.S. universities, most of whom study health or tobacco itself. In short, it’s a bunch of academics who research health and tobacco.

If you were hoping to see Rocky Patel, Lew Rothman or some sort of “cigar sommelier”—that’s a different panel for a different event.

I bring this up to inform you, not so that I can criticize the panel.

You very much should understand the perspective of the people who wrote this report and studied these issues. If you choose to either be ignorant of their backgrounds or to dismiss their views because of their backgrounds, you are doing yourself a disservice. The report exists and even if you don’t agree with all of the claims made in the report, there’s no doubt this will be used—like in the example of competing headlines above—by different groups on different sides of regulation of cigars.

3. Nothing Changes Tomorrow

Let’s just get this out of the way, the report has no bearing on how cigars are sold or regulated on March 11, 2022. It will almost certainly be used as evidence for future regulation, but nothing in here is binding or is set to become policy without FDA (or some other part of government) taking an additional, independent action.

4. The Main Takeaway: There’s Not Enough Data

I’ll get into some of the more interesting topics below, but if there’s one thing to take away from this 521-page report, it’s that the authors of this study oftentimes found there wasn’t data about “premium cigars” to look at, and as such, the report’s ability to draw conclusions is limited.

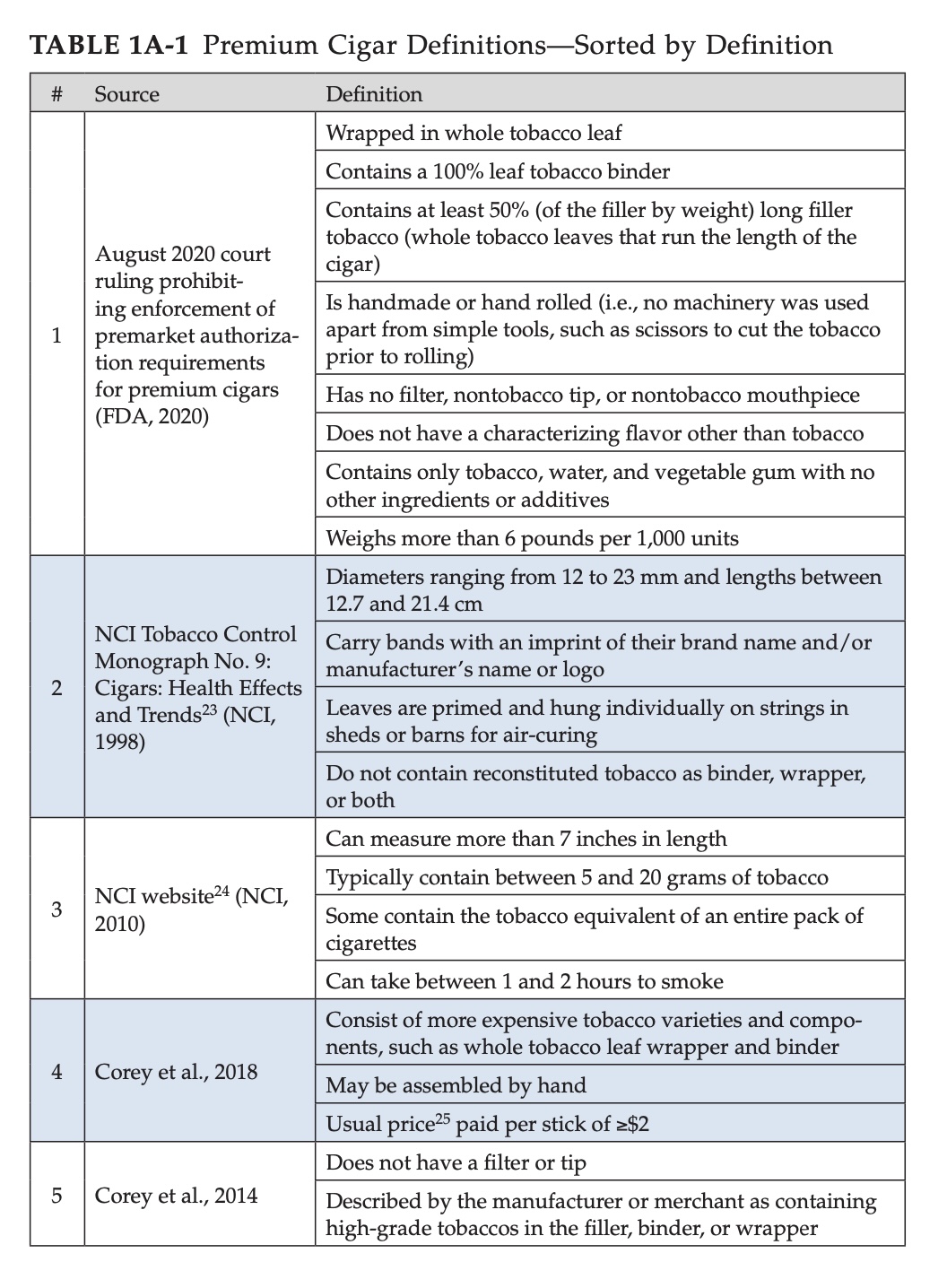

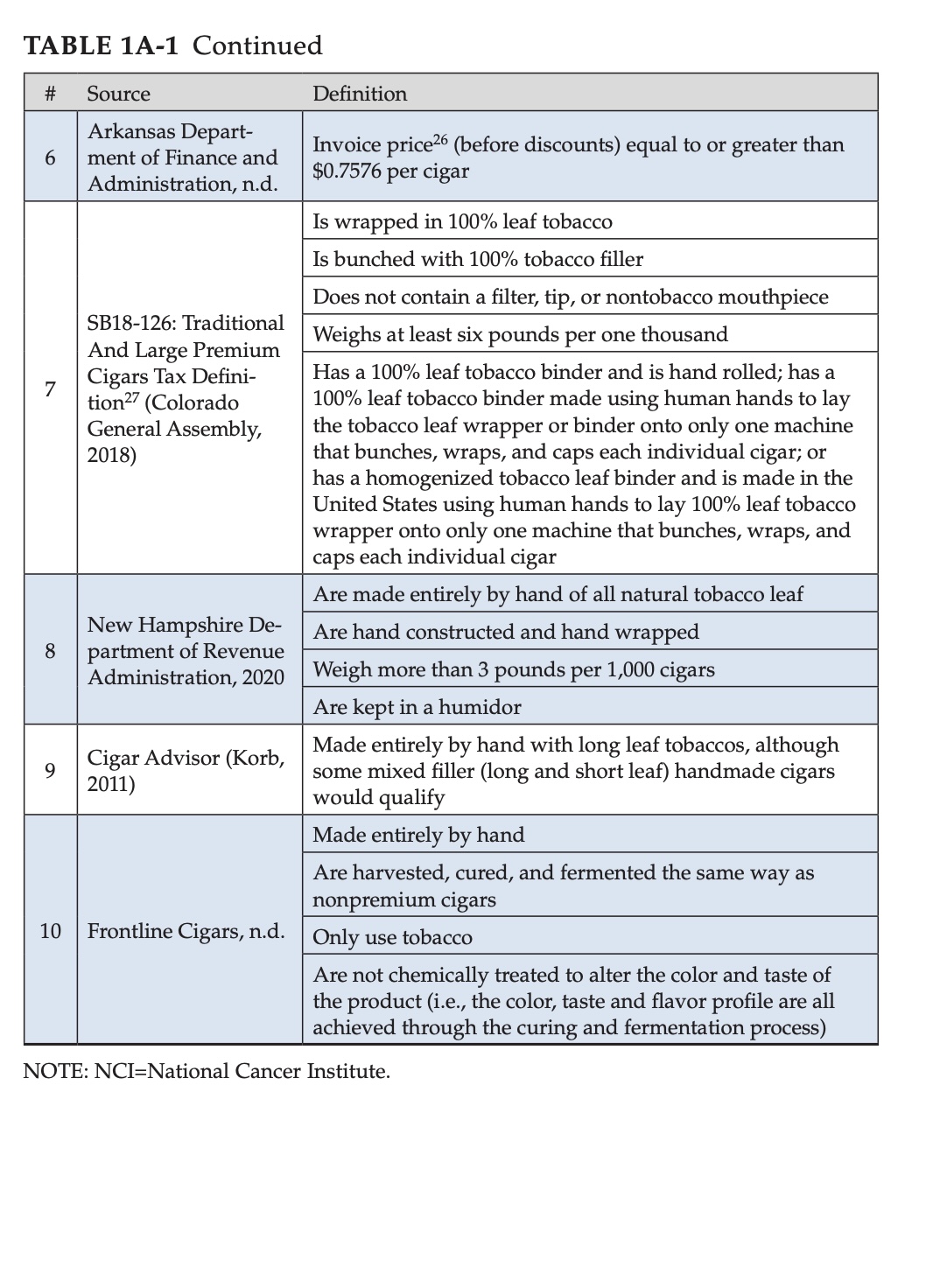

First, this should be of zero surprise. Not only are premium cigars a small part of the tobacco industry (the report suggests a steady 1 percent of the adult population in America “uses” premium cigars) but also, the authors make very clear that there’s not an established definition of “premium cigars.”

It’s worth pointing out that it’s not the case that a definition has never existed, rather, an established definition has not existed. For example, the two pictures above illustrate the various definitions that have been used to describe “premium cigars” and the chart above doesn’t even take into account that FDA’s own proposed definition of “premium cigars” changed between 2014 and 2020, notably the more recent definition does not include a $10 price requirement like the 2014 proposed definition required.

In layman’s terms, you can’t ask someone with red-green color blindness to tell you what model of car that red Tesla is. It’s not they can’t see the car is a Tesla, but they can’t see it’s red and so it’s impossible to know which car you are talking about.

As such, so much of the data is based on evidence that may not apply to “premium cigars.” And given that this panel wasn’t tasked with finding the ultimate definition of “premium cigar” to be used going forward, that liability remains. You’ll see examples where the report concludes things based on evidence of “cigars in general” or “large cigars,” but the authors make clear that qualitatively, those are not the same things as the most recent FDA definition of “premium cigar.”

5. My Main Takeaway: You Can See What You Want To See (And Not See What You Don’t Want To)

As pointed out in the intro with the two competing headlines, people of various backgrounds are going to have very different reactions to what’s actually in this report.

I suspect there are dozens of reasons why, but the main ones that stick out are:

- Your Perspective Colors Everything — A week ago one of the more knowledgeable people about FDA issues texted me and said “this will be bad” based on a paragraph or two outlining what would be discussed today. Then, four minutes after the report was released, he texted me “this is good.” As it turns out, his texts to me colored my opinions for a few minutes as I was trying to make sense of how page 16—what I was looking at 10:15 a.m. CST—was “good.”

- The Data Is Regularly Not Specific to “Premium Cigars” — Because the data is typically not specific to “premium cigars,” anyone can say “well, but if it was specific to premium cigars it would show X.”

- It’s 526 Pages, You Can Pick and Choose What You Want to Read — If you don’t read all of it—and in fairness to you, I’ve only read about 75 percent of the actual writing in a focused manner—then it’s real easy to just pick and choose a paragraph here and a paragraph there.

- There’s No Smoking Gun, One Way or the Other — If you are hoping to find some evidence that “premium cigars” aren’t dangerous, that’s not here. If you are hoping to find evidence of 12-year-olds buying “premium cigars,” that’s also not here. While I have not read every page yet, after getting through the meat of the report and some of its trimmings, there doesn’t appear to be anything that would qualify as a “smoking gun” for either side.

- Most of This is Not Based on New Data — I’m not someone who reads a ton of academic research but I’m slightly aware that most of the datasets mentioned in the report are not new. There are instances where the panel commissioned new studies specifically for this report, but those seem more exercises of taking already-gathered data and evaluating it through a different lens versus conducting new data gathering. The authors of the report acknowledged as much saying that there should be further studies of “premium cigars” on a wide range of topics, but that those will require new data gathering.

Perhaps nothing encapsulates this theory better than an answer from Dr. Steven Teutsch, the committee’s chair, who said this during a Q&A session:

Because of their ingredients, premium cigars are intrinsically as harmful as cigars and cigarettes. The actual health effects, though, are a combination of their intrinsic characteristics and how they are used (duration, frequency, depth of inhalation). Since only a small proportion of the population smokes premium cigars — and of those who do, most smoke only a small number each month — the aggregate health effects in the population are modest.

Depending on which sentence you read, it’s either good, bad or maybe not relevant for premium cigars.

6. What Does the Report Say About This?

You have questions, I may have the ability to copy and paste and/or summarize.

What does the report say “premium cigars” should be defined as?

First, it says that the committee itself wasn’t asked to come up with a definition.

Second, it came up with the following definition for its work:

For this report, a premium cigar is defined as having all of the following six characteristics: handmade, filler composed of at least 50 percent natural long-leaf filler tobacco, wrapped in whole leaf tobacco (i.e., not reconstituted tobacco), weighs at least 6 pounds per 1,000 units (i.e., 2.72 g per stick), no filters or tips, no characterizing flavor other than tobacco.

It should be noted, that’s more or less the same definition that FDA is currently using as part of the court agreement. There are some differences:

- NASEM’s panel does not require a 100 percent tobacco leaf binder; FDA’s does

- NASEM’s panel does not explicitly say “contains only tobacco, water, and vegetable gum with no other ingredients or additives” though FDA’s does

For what it’s worth, the committee also suggests that some parts of the definition probably needed to be changed. For example, it says that the weight requirements are probably too low given its own research.

What does the report say about how healthy “premium cigars” are?

This is very much you can see what you want to see.

On the positive side, it makes it clear that “premium cigars” are likely to have less of a negative health impact because most people that smoke them do so less oftentimes than other tobacco products.

Conclusion 5-5: There is strongly suggestive evidence that health consequences of premium cigar smoking overall are likely to be less than those smoking other types of cigars because the majority of premium cigar smokers are non-daily or occasional users and because they are less likely to inhale the smoke.

On the other hand, it says the ingredients are likely to be as dangerous as other types of tobacco products:

Conclusion 2-1: There is conclusive evidence that the addictive, toxic, and carcinogenic constituents of cigar tobacco in general are the same as those present in cigarette tobacco. There is strongly suggestive evidence that constituents of premium cigar tobacco are similar to constituents of other cigars because all tobacco contains nicotine, carcinogenic tobacco- specific nitrosamines, metals, and precursors to toxic and carcinogenic compounds formed during the combustion process.

But this is where that lack of data about “premium cigars” causes problems for the committee. Most of its scientific findings are not based solely on “premium cigars” but rather research on “cigars” or “large cigars.” The committee makes clear that there is not machines that can replicate a premium cigar smoker meaning it’s hard to produce controlled studies to evaluate many facets of “premium cigar” smoking like scientists can for cigarettes.

While most of the science is completely above my head, I do know that there’s a bit of sleight of hand taking place with the words used.

For example, here’s a sentence from the press release from NASEM:

The toxicants and carcinogens in premium cigar smoke are nearly identical to those in cigarette smoke, and they are capable of causing heart disease, cancers (lung, oral, head, and neck), respiratory diseases, and other adverse health effects, the report concludes.

And here’s a sentence from the report itself (page 10, emphasis mine):

Conclusion 2-2: There is conclusive evidence that the toxicants and carcinogens in cigar smoke in general are qualitatively the same as those in cigarette smoke. There is no reason to believe that toxicants and carcinogens in premium cigar smoke are any different from those in other types of cigars. Additionally, it is likely that the total toxic and carcinogenic constituent yields will increase with the mass of tobacco filler in the cigar.

Those two things aren’t the same.

I’m not accusing the committee of getting it “wrong,” rather, I think the takeaways of the science about “premium cigars” are very difficult to describe without the constant caveat that the data is almost always not specific to “premium cigars.” In fairness to the committee, they do a pretty good job of that in the report, hedging their statements at seemingly every page but that caution oftentimes goes away once this report becomes secondary and that will happen regularly, including with FDA.

There are a couple more pulled quotes in this article I wrote earlier that are related to health and you can see a similar pattern where the health claims are oftentimes about “cigars in general” and not “premium cigars.”

What does the report say about kids smoking “premium cigars?”

Nothing new. It relies on the PATH study data, which has been well-documented in the cigar world because of how favorable it reads for the industry. The two takeaways:

- 0.1 percent of people under the age of 18 reported using a premium cigar, a statistically insignificant number, meaning it qualifies outlier

- 0.6 percent of people who say they smoked a premium cigar in the last 30 days say they were under 18

What does the report say about cigar companies marketing to children?

Fortunately, not much at all, largely because there’s not much data according to the committee:

Only one study provides data on U.S. adults’ awareness of premium cigars, and research on youth awareness is less available.

A number of cigar companies are mentioned in the report in various contexts and Drew Estate gets mentioned as an example of a company that appears to be targeted “young people” but that’s not the same as “youth” or “children.”

What does the report say about flavored cigars?

It does talk about flavored cigars and I don’t think any of that discussion is surprising. Remember though, flavored cigars aren’t included in the report’s definition of “premium cigars” and as such, it’s not a focus.

What does the report say about what FDA should do next?

In short, come up with a definition of “premium cigar” and commission a number of studies about “premium cigars.”

If you are looking for a more exciting answer, the committee makes it clear, in multiple places, that is not its job:

However, the committee was not tasked with providing guidance on whether premium cigars should be considered separately from other cigar types for research or for regulatory purposes.

While the committee also was not tasked with providing policy recommendations, FDA may use its research recommendations to inform and evaluate policy and regulatory options for premium cigars.

7. Why is the PCA Taking a Victory Lap About “Premium Cigar Category?”

And to a lesser extent, J.C. Newman did too.

The reasons are probably many, but to me, it seems clear that:

- There’s not much in here that substantively changes what we knew about premium cigar regulation yesterday

- FDA is not bound by the report’s findings (see below)

- You probably want to take some positive from this

- This is something PCA and others have been asking FDA or Congress to do for more than a decade

- This could be good

It would be very helpful for the “premium cigar” industry for FDA to establish a definition of “premium cigars,” particularly under the guise that the products are different, or at the very least, consumed differently. The report provides evidence to the latter point and suggests that because of the different use patterns and the lack of data, “premium cigars” deserved to be in their own category if nothing more so that they can be studied differently.

I’d caution anyone to think that FDA classifying “premium cigars” is in and of itself a massive win because it functionally won’t change things by itself. What it will help with is the future of regulations.

Whenever someone on the anti-tobacco side claims “kids use cigars to roll blunts,” the premium side can say, “we aren’t that, FDA says this is what a premium cigar is and there’s no evidence of that.”

Whenever someone says “kids are attracted to cigars because of flavors,” the premium side can say, “we aren’t flavored.”

Sure, they could say that now, but it’s a lot easier when it’s a codified definition that FDA is using. Furthermore, it opens the door up to potentially receiving research about “premium cigars” that backs up the claims industry is making that could lead to lighter or less worse regulation. And it’s not just with FDA, a separate definition would be immensely helpful with industry’s outreach to Congress and also valuable on the state and local level.

There is some potential downside for companies like Drew Estate and others who sell large, flavored cigars. In many states, those cigars enjoy the tax status of traditional “premium cigars” and I could see some states adopting a new definition and forcing large, flavored cigars into a different tax category that could be punitive. That said, FDA is also trying to outright ban flavored cigars, so—bigger fish to fry.

8. It’s Fascinating to Think About the Study as Just as Study

Part of my week was planned around this report coming out today, which is a pretty good indication of the reverence I attached to the report. But if I take a step back and think about the report’s functional use, it’s fascinating to think about it as just a report or just a study.

If this was some sort of University of Michigan Tobacco Conference and the same authors produced the same exact study, minus the parts about how FDA commissioned the report, maybe halfwheel finds out about and writes about it? Maybe I decide that I have better things to do at 7:25 p.m., like my three-times pushed-back dinner reservation.

The study is a study and really nothing more. There’s a bit of outsized importance because FDA commissioned the study and particularly because it was commissioned as part of a lawsuit, but functionally, those two facts are likely to make little difference going forward.

In reality, FDA can easily cherry-pick what it wants from the study. If the cigar trade groups do their jobs correctly, there’s plenty that they can show off to members of Congress next week as reasons why cigars should be treated differently. But that would have happened if it was a hypothetical report from a mid-March conference in Ann Arbor, Mich.

9. FDA Isn’t Bound By the Report

Every time I’ve written about this report, I’ve made clear: FDA is not bound by anything in this report.

Sure, if the report was extremely friendly to the cigar industry, perhaps it would cause issues for FDA in a courtroom. But barring some really unforeseen and, in my opinion, impossible outcome, FDA does not have to adhere to anything in the report. It doesn’t have to adopt the definition, it doesn’t have to adopt a definition of “premium cigar.” It does not need to do more studies, it doesn’t need to do anything based on the report.

In fact, the report wasn’t even a requirement from the court; rather, this was one option FDA took in satisfying a broader court requirement: further study premium cigars.

10. FDA Hasn’t Satisfied the Court Order Yet So We Don’t Know When It Acts Next

FDA was required to do two things per the court order:

- Study “premium cigars” and their health/use/marketing impacts

- Study a “streamlined” process for premium cigar product approval

One could argue FDA hasn’t even completed the first one until it actually reviews what the NASEM report says. This report explicitly does nothing to satisfy the second report.

I think it will be telling to see the speed at which FDA moves forward with satisfying the court order and presenting the court with its findings and pathway forward.

11. The Most Likely Outcome is FDA Doing What it Said it Was Going to Do in 2016

For a number of reasons, the most likely outcome has always seemed that FDA would go back to court and say it was going to regulate all cigars the same. That’s what FDA did in 2016, that’s what it has been in court trying to defend, and after all, in the words of Dr. Gregory House, err Hugh Laurie, “People don’t change. For example, I’m gonna keep repeating ‘People don’t change.'”

Here’s what I said in December 2021:

To me, the likeliest scenario is that FDA ultimately decides to treat cigars like it said it would in 2016—i.e., just like every other tobacco product—but I probably wouldn’t even peg that at 50/50 odds. What I do know is that whatever world comes after this is very different than the one the cigar industry has lived under for the past five years. Even if FDA were to give the cigar industry the most favorable outcome and just drop product approval altogether—seemingly the least likely scenario—that’s a different world than the one we live in now because it removes a large chunk of uncertainty that has persisted for the past five years.

I probably would change the odds that it happens this year to closer to 50 percent given today’s news. But I’ll still leave open the possibility that an alternative, primarily a delay until 2023, or perhaps a wildcard beyond a delay, is on the table.

The takeaway for the industry on this point is the general baseline you hope for in tobacco regulation: it didn’t get any worse today and tomorrow is Friday.

You can download the report here.

Various groups and companies have put out statements links to them are as follows: