Once again, a federal court has thrown out FDA’s plans to require graphical warning labels on the packaging of cigarettes.

While the first lawsuit took place more than a decade ago in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia and later the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, the latest ruling comes from Judge John Campbell Barker of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas. Yesterday, he ruled in favor of the plaintiffs in R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. et al. v. U.S. Food & Drug Administration et al.

The case centered around an FDA rule issued in March 2020 that would have required cigarettes sold in the U.S. to come in packages that showed graphical warning labels that covered 50 percent of the front and rear of the packaging as well as 20 percent of any cigarette advertisements. While the graphics required for the 2020 rule were different from the 2011 rule that was thrown out by the D.C. court, the size requirements were the same.

While FDA issued the rule in March 2020, it had yet to go into effect.

In his decision, Barker rejected the government’s attempts to have the case dismissed on various technical grounds and instead ruled in favor of the plaintiffs’ claims on First Amendment grounds.

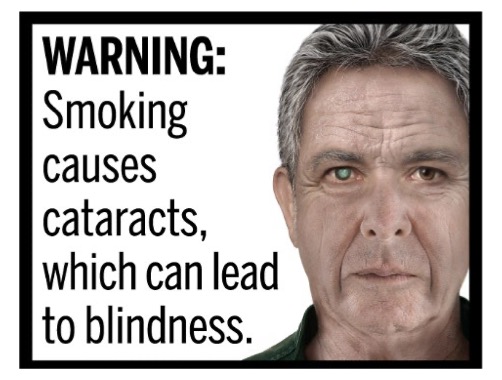

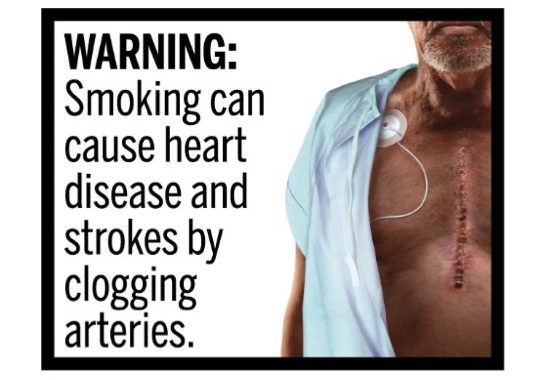

The meat of Barker’s decision is centered around whether the images FDA planned on requiring to be placed on cigarette packaging could be misinterpreted by consumers. The agency’s requirements called for various graphical warnings that showed potential health complications that could arise from smoking cigarettes such as heart disease, neck cancer, blindness and others. Barker found that these images and the accompanying texts could lead consumers to believe that the consequences of smoking were worse than the medical evidence suggests.

For example, Barker highlighted this image which warns that “smoking can cause heart disease and strokes by clogging arteries,” which showed a scar from open-heart surgery. However, he noted that commenters provided evidence to FDA that showed that “in-patient interventions for heart disease are 2.5 times more common than open-heart surgery,” something the FDA did not dispute.

Additionally, this image showed advanced damage caused by untreated cataracts, something that is typically treated before it gets to this stage. For these and other images, Barker pointed out that a consumer of the messages could reasonably interpret that the health issues shown in the images were the most common result, even if the medical evidence shows that a less harsh health issue is the likelier outcome.

This is key because of the American legal standards for requiring warning labels on products, something known as “compelled speech.”

In 1985, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Counsel of Supreme Court of Ohio that the government could use compelled speech to protect consumers from deception but that the information in the required warnings must be accurate, “purely factual and uncontroversial.” Barker found the images to fail the “purely factual” part of the test because consumers could reasonably interpret many different meanings from the images. This in turn calls into question whether the warnings are “accurate” per the standards established in Zauderer.

Furthermore, he found that the government failed to meet the burdens set out in Central Hudson Gas & Electric Corp. v. Public Service Commission, a 1980 Supreme Court ruling, because the government’s interest in warning the public about the dangers of smoking could be addressed through other efforts such as an advertising campaign or by smaller, text-based warning labels.

The Department of Justice, which represents FDA in litigation, argued that the case should be thrown out due to a lack of standing by the plaintiffs, as well as that the case should be moved to a different court. Barker rejected both of these arguments.

Even if the government had won, the victory would have had no immediate impact on premium cigars as the graphic warning label rule would have only applied to cigarettes. In 2014, FDA issued the Deeming Rule, which required cigar companies to place text-based warning labels on cigar packaging and advertising, however, cigar companies sued and a federal appeals court ruled that FDA’s text-based warning labels for cigars were illegal. It’s unclear whether FDA would have tried—like many other countries—to apply these graphical warning labels to cigar packaging and advertisements.

Despite all this, a small number of cigar companies—though many of the largest cigar companies—are required to put small warning labels on their products due to a 2000 agreement between those companies and the U.S. Federal Trade Commission. The vast majority of cigar companies are not subject to this agreement.

In July, as part of that same cigar-related lawsuit, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia ruled against FDA regarding its regulation of premium cigars. The final order of that lawsuit is still pending, but the outcome of that case could remove premium cigars from FDA regulation altogether, requiring the agency to restart the process of getting premium cigars to be regulated.